Pánfila Domestic Violence HOPE Foundation

Brain Donation Initiative

The Domestic Violence and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Connection

What is CTE?

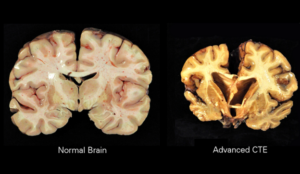

Currently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) conjures up several stark images of dramatic concussions to the head from combat and collision sports that can lead to a downward spiral into depression, dementia, rage, and tragically, suicide.[1] However, brain science has discovered CTE in athletes who have never been diagnosed with a concussion. In fact, current scientific evidence suggests that repetitive head impacts, including non-concussive head impacts and not concussions, are the driving force behind CTE. [2]

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy is a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people with a history of repetitive non-concussive head impacts. The repeated brain trauma triggers progressive degeneration of the brain tissue, including the build-up of an abnormal protein called tau. These changes in the brain can begin months, years, or even decades after the last brain trauma [3, 4]. The brain degeneration is characterized by CTE’s pathology which has four stages of severity and is associated with cognitive, mood, sleep, physical, memory loss, suicidality, Parkinsonism, and other manifestations. [5]

CTE has been known to affect boxers since the 1920’s when it was initially termed “punch drunk syndrome.”[6] In 1937, the term “dementia pugilistica” was introduced. [7] Over a decade later, in the first of two important studies on “dementia pugilista” in boxers in 1949, the term punch drunk syndrome was dropped in favor of “chronic progressive traumatic encephalopathy,”[8, 9] now widely referred to as CTE.

In recent years, reports have been published of neuropathologically confirmed CTE found in other athletes, including football and hockey players (playing and retired), as well as in military veterans who have a history of repetitive brain trauma.[10, 11] CTE is not limited to current professional athletes or military/veterans; it has also been found in athletes who did not play sports after high school or college. [12]

Domestic Violence and CTE

What is less known is that domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers are also at risk of CTE as a result of the types of abuse they sustain during domestic violence episodes, some for years and decades.

There are only a few domestic violence brains that have been postmortem examined for CTE. The first case was documented in 1990 in a letter, titled “Dementia in a Punch-Drunk Wife,” in The Lancet.[13] It profiled a 76-year-old woman whose relatives reported that her husband had been violent towards her for many years and she was often seen with cuts and bruises. The woman was admitted to hospital unconscious after being found at home with multiple injuries. She had rib fractures, multiple bruises and abrasions to the head, and signs of left-sided weakness. She had a history of a stroke and had become demented over the past few years. She died in the hospital 10 months after admission and necropsy revealed abnormal thickening of the ears, resembling the “cauliflower ears” of pugilists. The letter was followed by a post-mortem description of a battered woman with a pathology found in deceased boxers with CTE.

The Lancet connected two patient populations—boxers and domestic violence victims—together for the first time to punch-drunk disease. Both conditions, then referred to as punch-drunk disease and battered woman syndrome respectively, linked domestic violence and CTE. However, this unprecedented finding was not met with the same level of advocacy, attention, and allocation of resources that contact sports and military received when CTE was found among these respective populations. In fact, little advocacy has taken place to focus on it.

Decades later, since the the publication of “Dementia in a Punch-Drunk Wife,” equally devastating is the neuropathology report of María P. Garay, the inspiration for This Hits Home and this organization. During the filming of This Hits Home, Dr. Garay-Serratos learns from Dr. Ann McKee (CTE world-renowned brain scientist and Director of Boston University CTE Center), in real time, that her mother’s brain did exhibit the damage associated with CTE. Dr. McKee further explains that the case is extreme, worse than any former NFL player’s or veteran’s brain she has examined. It is the first public case of CTE in a domestic violence female victim.

These findings point to a potential silent and ignored population living with CTE: Domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers. Sadly, brain science has largely ignored the domestic violence population and thus, leaving them in the dark. Most are unaware that the symptoms they are experiencing may be associated with CTE.

Based on domestic violence statistics, it is highly likely that many victims, survivors, and thrivers of domestic violence have suffered repetitive non-concussive impacts and concussions during DV episodes, like María did. At both the national and global levels, few ever speak about the silent and unrecognized epidemic of TBI and potentially CTE in the domestic violence population. Among researchers and the healthcare field at large, this area of science has received minimal attention despite the historic high rates of domestic violence and even higher ones during the Shadow Pandemic amidst the Covid-19 Pandemic.

For further information about the latest science on CTE link to the Concussion Legacy Foundation or the BU CTE Center’s website.

The Domestic Violence and Traumatic Brain Injury Connection

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), like CTE, is of great health and public concern among individuals in contact sports and veterans. There is also emerging and frightening realization that non-concussive head impacts and concussions have an enduring and potentially devasting effect on our children and youth that participate in contact sports.[14] In the United States (US), approximately 2.8 million head injuries are reported annually.[15]. However, these numbers underestimate the occurrence of TBIs because they do not account for individuals who did not receive medical care, had outpatient or office-based visits, or persons who received care at a federal facility, such as persons serving in the US military or those seeking care at a veterans affairs hospital (16), and domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers.

Women

While much of the focus on TBI has centered on athletes and military veterans, emerging data indicates that DV victims constitute an under-represented cohort. One in three women will experience DV in their lifetime[17] with higher rates among African American (53.6%), multiracial (63.8%), Indigenous (57.7%),[18] American Indian and Alaska Native (84.3%), Native American,[19] and other ethnic minority and marginalized women due to social injustice and other intersectionality issues. Latinas make up 9.6% of the US population [20] but DV prevalence ranges from 44% to [21] 83% with 48% [22] reporting DV increasing after immigration to the US due the same issues as other marginalized women face including disparities and intersectionality factors . The COVID Pandemic resulted in even higher incidences of DV in the US and world-wide due to a variety of variables associated with confinement.[23]

Immigrant Women

Immigrant women experience abuse at higher rates, 13.8% to 93%, than the general U.S. population.[24] When U.S. citizens are married to foreign women, the abuse rate is approximately three times higher than the abuse rate in the general population.[25]

Research conducted among female domestic violence victims reporting TBI is telling and alarming. In 2002, a landmark study of women in three domestic violence shelters found [26]:

- 92 percent had been hit in the head by their partners, most more than once;

- 83 percent had been both hit in the head and severely shaken; and; and

- 8 percent of them had been hit in the head over 20 times in the past year.

Other research [27, 28] has found similar rates of TBI among female domestic violence victims.

It is important to note that it is unclear if immigrant women and other vulnerable categories of women were included in these studies.

Together, these statistics amount to approximately 55 million women experiencing DV, of which 44 million demonstrate signs of TBI. Alone, this is 17-18 times greater than the published incidence of TBI. This is just in the US. Globally, no DV-TBI data is collected but the DV-TBI numbers are similar or higher given domestic violence statistics.

Children

Moreover, in up to 60 percent of homes where women are beaten, children are also beaten.[29] As many as 15.5 million American children live in families in which DV has occurred during the past year.[30] It is estimated that of the children who suffer abuse, over 60 percent of them also experience TBI.[31] Children have the highest rate of emergency department visits for TBI of all age groups. Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death in injured children.[32] Additionally, the most consistent predictor of domestic violence is having experienced abuse as a child, [33] compounded with the enduring emotional symptoms of TBI is increased aggression, which further impacts future generations and communities at large. Further research will distinguish whether this pattern or perpetuated violence between generations is based on emotional effects or traumatic injury to the brain.

Men with Abusive Tendencies

Furthermore, one in seven men will experience severe physical violence by an intimate partner.[34]. However, the incidence of brain trauma among men who have experienced domestic violence – whether from a parent/guardian or from an intimate partner — has not been studied in-depth. Among men who engage in domestic violence behavior, a study found that 61 percent had histories of head injury.[35] A follow-up study found that an overwhelming majority, 93 percent, of head-injured domestic violence abusers had endured their head injury prior to the first occurrence of marital abuse, with 74 percent of these men receiving the head injury before the age of 16.[36]

Other research [37] on men who abuse with history of traumatic brain injury has found similar findings. As with DV-TBI research on women, it is unclear if immigrant men or other disenfranchised groups of men were included in this line of research. Thus, domestic violence intensifies the impact of TBI as a healthcare epidemic.

For more information about Traumatic Brain Injury please click here.

Most Immigrants and other Disenfranchised Communities Do Not Speak about Domestic Violence or Seek Support for it

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg as these low numbers do not account for the 70 percent of DV cases that go unreported [38] especially among immigrants for a variety of intersectionality issues including institutionalized forms of racism, discrimination, sexism, language barriers, documentation status, and other challenges.[39]

Only 15 Percent of DV Victims and Survivors Seek Help

In the United States, research has consistently found that men and women are significantly more likely to disclose instances of violence to informal rather than formal sources of support. [40] In fact, only 15 percent of DV victims and survivors seek help from police and doctors. [41] Similar findings have been found globally. [42] Minority populations tend to show higher levels of seeking help from informal networks such as clergy, friends, family, online resources, and neighbors for issues [43, 44] for reasons of health disparity and other intersectionality issues. [45]

Domestic Violence Expected to Rise

The national economic cost of domestic is estimated to be over twelve billion dollars per year. The number of individuals affected is expected to rise over the next 20 years. [46]

Pánfila Domestic Violence HOPE Foundation

Brain Donation Initiative

Pánfila and the Boston University Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (BU CTE) Center and the UNITE Brain Bank are responding to the urgent call for action with the Pánfila Domestic Violence HOPE Foundation Brain Donation Initiative, which will enable scientific research by encouraging brain donation and future pledges for brain donation. However, we are strategically seeking to collaborate with other institutions passionate about developing specific brain bank/s for the advancement of science to understand the sequelae of DV-CTE, DV-TBI, and other brain neurological health issues impacting domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers to develop treatments, identify biomarkers, and other critical scientific issues. Advancing science is a foundational objective that is critical for launching a nationwide, comprehensive public health education campaign designed to improve quality of life for those impacted by domestic violence TBI and potentially CTE and/or other neurological diseases.

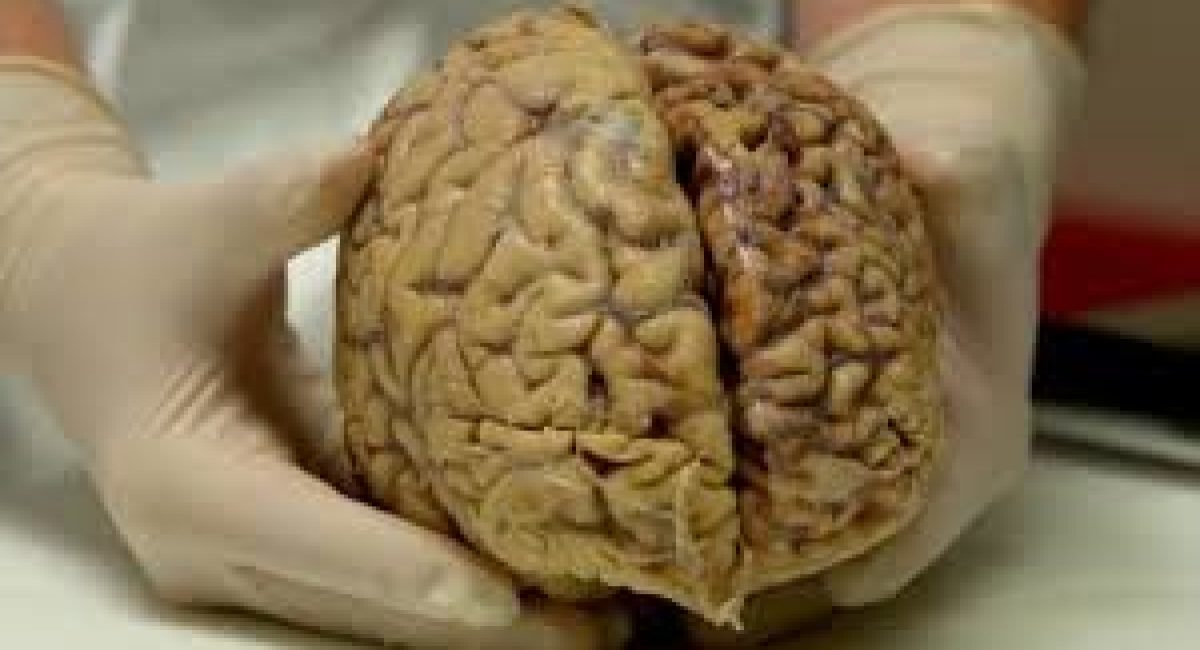

Pánfila’s highest scientific priority is to promote brain donation for research by domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers. Additional research is needed to further characterize the relationship between domestic violence and the resulting neuropathology, including CTE.

Pánfila Domestic Violence HOPE Foundation is supporting this research by affiliating with the UNITE Brain Bank to encourage brain donation among individuals impacted by brain injury and/or head trauma as a result of domestic violence. Brain donation will enable a comprehensive post-mortem brain analysis by a team of experienced neuropathologists at the VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine. Currently, CTE and many other neurodegenerative diseases can only be diagnosed by post-mortem examination of brain tissue.

The Pánfila Domestic Violence HOPE Foundation will support the BU CTE Center, the UNITE Brain Bank and other scientific institutions with the following efforts:

- Encourage brain donation by domestic violence victims, survivors, and thrivers and facilitate future brain donation pledges

- Compile research-based evidence of connection between abuse and neuropathological injury

- Educate and train the healthcare field, first responders, social service system, and others serving DV victims, survivors, and thrivers to identify domestic violence and related brain injury and head trauma to provide support

- Help develop potential treatments and prevention strategies for domestic violence-based neurotrauma

- Advance scientific knowledge and public awareness of relationship between domestic violence and brain pathology

- Advocate for victims, survivors, and thrivers of DV-TBI, DV-CTE, and other forms of brain trauma and injury

The Concussion Legacy Foundation partnered with BU CTE Center and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to found the UNITE Brain Bank to conduct high-impact, innovative research on CTE and neurodegenerative diseases resulting from brain trauma primarily in athletes and military personnel as well as victims, survivors, and thrivers of domestic violence and others. Their mission is to conduct research on aspects of CTE and other neurodegenerative diseases including neuropathology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, risk factors, genetics, biomarkers, detection during life and methods of prevention and treatment.

A Precious Gift

Without the gift of brain donation, research to understand the consequences of brain trauma would not be possible. The identity of donors is confidential and protected by IRB rules and HIPAA laws. Through this research, increased public awareness of the relationship between domestic violence and brain trauma will encourage efforts to end domestic violence. There is no cost to the families for brain donation to the BU CTE Center and UNITE Brain Bank. All funding to the BU CTE Center and UNITE Brain Bank is through grants from federal agencies, private philanthropy and institutional support from VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine.

The identity of donors is confidential and protected by both IRB rules and HIPAA laws. However, many donors have chosen to allow the CTE Center to release their names to draw attention to this important work.

For additional information, please contact:

Sophia Nosek at snosek@bu.edu. For imminent brain donation inquiries, please call the UNITE Brain Bank’s 24/7 voicemail/pager at 617-992-0615. Brain donation is a time-sensitive process, so we must be in touch with the legal next-of-kin or medical examiner as soon as possible around the time of death. Families are encouraged to express their intent to donate to the UNITE Brain Bank to coroners, investigators, medical examiners, and funeral directors.

Please review our brain donation brochures and FAQ for more information.

____________________________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Peskind, E. R., Brody, D., Cernak, I., McKee, A., & Ruff, R. L. (2013). Military- and sports-related mild traumatic brain injury: clinical presentation, management, and long-term consequences. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 74(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12011co1c

[2] Daneshvar, D. H., Nair, E. S., Baucom, Z. H., Rasch, A., Abdolmohammadi, B., Uretsky, M., Saltiel, N., Shah, A., Jarnagin, J., Baugh, C. M., Martin, B. M., Palmisano, J. N., Cherry, J. D., Alvarez, V. E., Huber, B. R., Weuve, J., Nowinski, C. J., Cantu, R. C., Zafonte, R. D., Dwyer, B., … Mez, J. (2023). Leveraging football accelerometer data to quantify associations between repetitive head impacts and chronic traumatic encephalopathy in males. Nature communications, 14(1), 3470. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39183-0

[3] McKee, A. C., Mez, J., Abdolmohammadi, B., Butler, M., Huber, B. R., Uretsky, M., Babcock, K., Cherry, J. D., Alvarez, V. E., Martin, B., Tripodis, Y., Palmisano, J. N., Cormier, K. A., Kubilus, C. A., Nicks, R., Kirsch, D., Mahar, I., McHale, L., Nowinski, C., Cantu, R. C., … Alosco, M. L. (2023a). Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA neurology, 80(10), 1037–1050. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907

[4]McKee, A. C., Stein, T. D., Huber, B. R., Crary, J. F., Bieniek, K., Dickson, D., Alvarez, V. E., Cherry, J. D., Farrell, K., Butler, M., Uretsky, M., Abdolmohammadi, B., Alosco, M. L., Tripodis, Y., Mez, J., & Daneshvar, D. H. (2023b). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta neuropathologica, 145(4), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-023-02540-w

[5]Alosco, M. L., White, M., Bell, C., Faheem, F., Tripodis, Y., Yhang, E., Baucom, Z., Martin, B., Palmisano, J., Dams-O’Connor, K., Crary, J. F., Goldstein, L. E., Katz, D. I., Dwyer, B., Daneshvar, D. H., Nowinski, C., Cantu, R. C., Kowall, N. W., Stern, R. A., Alvarez, V. E., … Mez, J. (2024). Cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric correlates of regional tau pathology in autopsy-confirmed chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Molecular neurodegeneration, 19(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-023-00697-2

[6] Changa, A. R., Vietrogoski, R. A., & Carmel, P. W. (2018). Dr Harrison Martland and the history of punch drunk syndrome. Brain : A Journal of Neurology, 141(1), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx349

[7] Millspaugh, J.A. (1937). Dementia pugilistica. U S Naval Medical Bulletin, 35, 297–303.

[8] Critchley, M. (1949). Punch drunk syndrome: the chronic encephalopathy of boxers. In Neurochirurgie Hommage à Clovis Vincent. Paris: Maloine. In I. Donaldson, C. Marsden, S. Schneider, & K. Bhatia (Eds.) (2012). Marsden’s book of movement disorders (637). London: Oxford University Press.

[9] Critchley, M. (1957). Medical aspects of boxing, particularly from a neurological standpoint. British Medical Journal, 1(5015), 357–362. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5015.357

[10] Mckee, A. C., Abdolmohammadi, B., & Stein, T. D. (2018). The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Handbook of clinical neurology, 158, 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63954-7.00028-8

[11] Priemer, D. S., Iacono, D., Rhodes, C. H., Olsen, C. H., & Perl, D. P. (2022). Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in the Brains of Military Personnel. The New England journal of medicine, 386(23), 2169–2177. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2203199

[12] Bieniek, K. F., Blessing, M. M., Heckman, M. G., Diehl, N. N., Serie, A. M., Paolini, M. A., 2nd, Boeve, B. F., Savica, R., Reichard, R. R., & Dickson, D. W. (2020). Association between contact sports participation and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a retrospective cohort study. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland), 30(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12757

[13] Roberts, G. W., H. L. Whitwell, Peter R. Acland, & C. J. Bruton., (1990). Dementia in a punch-drunk wife. Lancet, 335 (8694), 918–919.

[14] Waltzman, D., Womack, L. S., Thomas, K. E., & Sarmiento, K. (2020). Trends in Emergency Department Visits for Contact Sports-Related Traumatic Brain Injuries Among Children – United States, 2001-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(27), 870–874. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6927a4

[15] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[16] Faul, M., Xu, L., Wald, M.M., & Coronado, V.G. (2010). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

[17] Leemis R.W., Friar N., Khatiwada S., Chen M.S., Kresnow M., Smith S.G., Caslin, S., & Basile, K.C. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[18] Office of Women’s Health (OASH). (2023). Violence against immigrant and refugee women. Retrieved from https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety/other-types/immigrant-and-refugee-women

[19] Rosay, A.B. (2016). Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men: 2010 Findings from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. NCJ 249736.

[20] United Stated Census Bureau (2021). Hispanic or Latino, and not Hispanic or Latino by race. https://data.census.gov/table?q= hispanic&t=-09+-+All+available+Hispanic+Origin:400+-+Hispanic +or+Latino+(of+any+race)&tid=DECENNIALPL2020.P2 U

[21] See for example:

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M., & Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https:// www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- Gonzalez, Benuto, L. T., & Casas, J. B. (2020). Prevalence of interpersonal violence among Latinas: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018806507

[22] Gonzalez, Benuto, L. T., & Casas, J. B. (2020). Prevalence of interpersonal violence among Latinas: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018806507

[23]See for example:

- UN Women (2020).Intensification of Efforts To Eliminate All Forms of Violence Against Women: Report of The Secretary-General (2020). https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/07/a-75-274-sg-report-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls

- UN Women and UNDP (2021). COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker. https://data.undp.org/gendertracker/

[24] See for example:

- Barkho, E., Fakhouri, M., & Arnetz, J. E. (2011). Intimate partner violence among Iraqi immigrant women in Metro Detroit: A pilot study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(4), 725–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9399-4

- Carson, S. (Feb. 24, 2023). Why immigrant women are especially vulnerable to domestic violence. https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/2023/02/24/why-immigrant-women-face-an-increased-risk-of-domestic-violence/69903721007/

- Finno-Velasquez, M., & Ogbonnaya, I. N. (2017). National estimates of intimate partner violence and service receipt among Latina women with child welfare contact. Journal of Family Violence, 32(7), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9912-9

- Kimber, M., Henriksen, C. A., Davidov, D. M., Goldstein, A. L., Pitre, N. Y., Tonmyr, L., & Afifi, T. O. (2015). The association between immigrant generational status, child maltreatment history and intimate partner violence (IPV): Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(7), 1135–1144. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00127-014-1002-1

- Munisamy, G. (2010). Impact of intimate partner violence on health in Asian Indian immigrant women (2010-99040-484; Issues 8-B) [ProQuest Information & Learning]. APA PsycInfo. https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=https://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2010- 99040-484&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Office of Women’s Health (OASH). (2023). Violence against immigrant and refugee women. Retrieved from https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety/other-types/immigrant-and-refugee-women

- Orloff, L.E., Jang, D. & Klein, C.F. (1995). With No Place to Turn: Improving Advocacy for Battered Immigrant Women. Family Law Quarterly,29(2):313.

- Rai, A., & Choi, Y. J. (2021). Domestic violence victimization among South Asian immigrant men and women in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17–18), NP15532– NP15567. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211015262

[25] Carson, S. (Feb. 24, 2023). Why immigrant women are especially vulnerable to domestic violence. https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/2023/02/24/why-immigrant-women-face-an-increased-risk-of-domestic-violence/69903721007/

[26] Jackson, H., Philp, E., Nuttall, R.L. & Diller, L. (2002). Traumatic Brain Injury: A Hidden Consequence for Battered Women. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 33, 1, 39-45.

[27] Liu, L. Y., Bush, W. S., Koyutürk, M., & Karakurt, G. (2020). Interplay between traumatic brain injury and intimate partner violence: data driven analysis utilizing electronic health records. BMC women’s health, 20(1), 269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01104-4

[28] Monahan, K. (2018). Intimate Partner Violence, Traumatic Brain Injury, and Social Work: Moving Forward. Social work, 63(2), 179–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swy005

[29] Kelleher, K., Gardner, W., Coben, J., Barth, R., Edleson, J. L., & Hazen, A. (2012). Children and Domestic Violence Services (CADVS) Study: Co-Occurring Intimate Partner Violence and Child Maltreatment in the United States, 2003-2004. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 02-29. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04569.v1

[30] McDonald, R., Jouriles, E.N., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., Caetano, R., & Green, C.E. (2006). Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology, (1),137-142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. PMID: 16569098.

[31] Theodorou, C.M., Nuño, M., Yamashiro, K.J., & Brown, E.G. (2021). Increased mortality in very young children with traumatic brain injury due to abuse: A nationwide analysis of 10,965 patients. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 56(6):1174-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.02.044. Epub 2021 Feb 24. PMID: 33752910; PMCID: PMC8131228.

[32] Araki, T., Yokota, H., & Morita, A. (2017). Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Characteristic Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Neurologia medico-chirurgica, 57(2), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.ra.2016-0191

[33] Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32(8), 797-810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004

[34] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[35] Rosenbaum, A. & Hoge, S.K. (1989). Head injury and marital aggression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(8):1048–1051.

[36] Rosenbaum, A., Hoge S.K., Adelman, S.A., Warnken, W.J., Fletcher, K.E., & Kane, R.L. (1994). Head injury in partner-abusive men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(6), 1187–1193.

[37] Akerele, F. A., Murphy, C. M., & Williams, M. R. (2017). Are Men With a History of Head Injury Less Responsive to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Intimate Partner Violence?. Violence and victims, 32(3), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-16-00005

[38] Tjaden, P. G. & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence. National Violence Against Women Survey, National Institute of Justice (U.S.). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21858

[39] Office of Women’s Health (OASH). (2023). Violence against immigrant and refugee women. Retrieved from https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety/other-types/immigrant-and-refugee-women

[40] Sylaska, K. M., & Edwards, K. M. (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 15(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10. 1177/1524838013496335

[41] Fanslow, J. L., & Robinson, E. M. (2010). Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by a representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(5), 929–951. https://doi.org/10. 1177/0886260509336963

[42] Goodson, A., & Hayes, B. E. (2021). Help-seeking behaviors of intimate partner violence victims: A crossnational Analysis in developing nations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), NP4705–NP4727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518794508

[43] Huecker, M. R., King, K. C., Jordan, G. A., & Smock, W. (2023). Domestic Violence. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

[44] Kyriakakis, S. (2014). Mexican immigrant women reaching out. Violence against Women, 20(9), 1097–1116. https://doi.org/10. 1177/1077801214549640.

[45] Monterrosa, A. E. (2019). How race and gender stereotypes influence help-seeking for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0886260519853403.

[46] Hulley, J., Bailey, L., Kirkman, G., Gibbs, G. R., Gomersall, T., Latif, A., & Jones, A. (2023). Intimate Partner Violence and Barriers to Help-Seeking Among Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic and Immigrant Women: A Qualitative Metasynthesis of Global Research. Trauma, violence & abuse, 24(2), 1001–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211050590